Ray Taylor on Raku ceramics

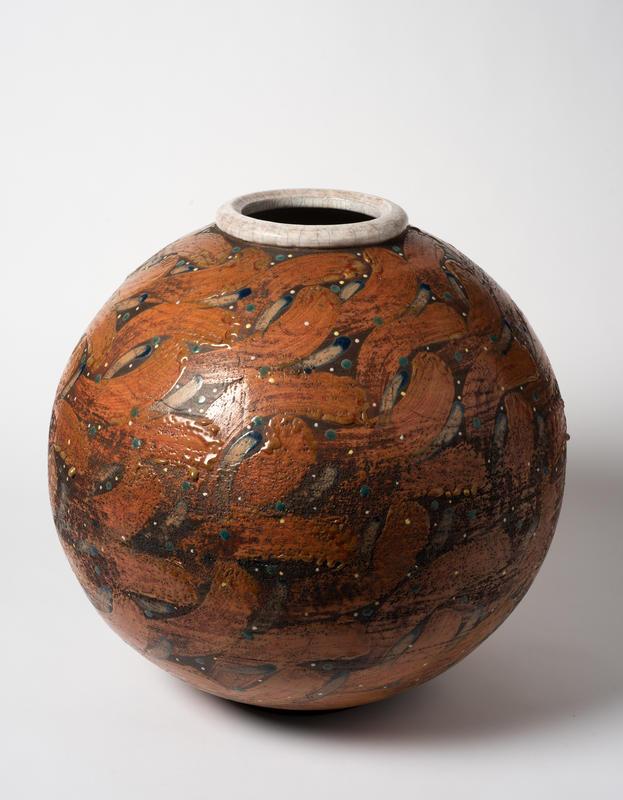

Amongst CAM’s diverse collection of ceramics is a handsome large raku pot made by Ray Taylor.

Sphere 1986 is a distinctive work with lively comet-like slip brush strokes and raised dots in contrasting colours evenly covering the entire spherical surface. Taylor’s work has evolved from and is a personal interpretation of the Japanese tradition of raku ceramics. Taylor has recently offered two smaller works to the Castlemaine Art Museum. These spherical pots are similarly decorated with even hand applied brush strokes interspersed with small dots or smaller comet-like shapes layered like a web across the spherical surface. Taylor’s creative output as a full-time practicing artist includes ceramics, sculpture, painting, and digital art. However, Taylor is more generally known for his raku work. For this Reflection CAM invited Ray Taylor to introduce his interest in raku ware.

Initially I was strongly influenced by traditional raku ceramics developed in Japan. I was sympathetic to the Japanese philosophy associated with raku, and the unique way of making the ceramics. I was also influenced by western ceramists who adopted and extended this traditional raku approach. My work has evolved both technically and aesthetically from this base to create my own personal style of ceramics.

I found the process of making raku ceramics an exciting and a rewarding way to work. It was dramatically appealing with the rapid firing, removing red hot pots from a kiln, with billowing smoke, and the sudden appearance of rich colour when the pots were doused in water and scrubbed. There is a close visceral, hands-on involvement in every aspect of creating raku ceramics.

The ongoing and immediate feedback from glaze firing an individual ceramic in a relatively short time encourages rapid exploration and the development of ideas. It also encourages the ceramist to experiment and take chances, both aesthetically and technically. Each ceramic can provide a rewarding and satisfying experience as it is completed.

Raku ceramics were created in seventeenth century Japan. They reflected Japanese culture, society, and events; including the Japanese tea ceremony, philosophical approach and a natural disaster.

The Japanese tea ceremony was a highly ritualized form of quiet meditation, whereby a small number of participants became completely absorbed in the preparation and drinking of tea in a natural and secluded setting. The philosophy and practices associated with the tea ceremony and raku emphasized direct individual expression and activity.

The unique method of firing raku ceramics was developed in response to a natural disaster in Japan. Tokyo was devastated by an earthquake in the 17th century. Millions of roof tiles were shattered. Tile makers replaced these tiles quickly by removing the red-hot tiles from the kiln, and then reloading the kiln after rapid cooling. Raku ceramists adopted and adapted this technique and incorporated it into their glaze firing method.

Japanese raku ceramists made simple and unpretentious bowls and caddies specifically for the tea ceremony. The ceramics were made by hand, emphasizing a natural and immediate physical expression. The ceramics were then bisque fired. A single ceramic was glazed and fired very quickly in a small, wood fired brick kiln. When the glaze was seen to have melted, the ceramic was removed from the kiln, with tongs, while red hot. The rapid cooling in the open air caused extensive crazing in the glaze. The glazed surface was rubbed with tea to darken and emphasize the crazing. After removal, another ceramic could be placed in the still hot kiln and the cycle repeated more quickly.

A single individual could be directly and intimately involved in all aspects of creating and firing raku ceramics. The process and the equipment are well within the capabilities of a single person. This was in direct contrast to the traditional ways of making pottery in Japan. Mainstream Japanese pottery was a group effort with many highly skilled craftsmen, a separation of tasks at all stages of production, mass output and the use of sophisticated processes and equipment.

The tea ceremony and the making of raku ceramics were usually practiced by the cultural elite in Japanese society. Raku bowls and individual rake ceramists were and are still highly regarded and esteemed in Japanese society.

Initially, the raku adopted in the West was similar to the Japanese raku. However, raku ceramics in the West quickly evolved and diversified in a number of areas that were very different from the raku practiced in Japan. Individual ceramists developed their own interpretation of raku, to produce one off creations which were appreciated as works of art. Output was diversified by individual ceramists resulting in a wide range of personal styles. Raku was now seen [in Japan and internationally?] as an individual creation, not tied to function or the tea ceremony Might you say

Technical innovations were also introduced. Today, raku ceramics are often fired in kilns with a metal casing, lined with fibre insulation, and propane gas used as fuel. A post firing step was [has been] introduced involving smoking after glaze firing. A red-hot pot was [is?] removed from the kiln with tongs and placed in a bin full of newspaper or sawdust. The resultant flames were [are] then snuffed out with a lid producing heavy smoke. This smoking blackened [blackens] the glaze crazing and unglazed areas. The ceramic was [is] then cooled with water and scrubbed to remove the smoke carbon and to expose the glaze colours.